Ever watched a child talking to Elmo or Dora like they’re old friends? That’s not just adorable—it’s psychology in action. These seemingly one-sided connections with media figures are called parasocial relationships, and they begin developing early in life as part of how kids learn about relationships in general (Hartup, 1989).

From the moment children start bonding with parents or caregivers, they’re laying the groundwork for all future social interactions. But their social world isn’t limited to real people. Many kids have imaginary friends or talk to stuffed animals, and that’s completely normal. In fact, it’s an important part of learning how to relate to others (Singer & Singer, 2005).

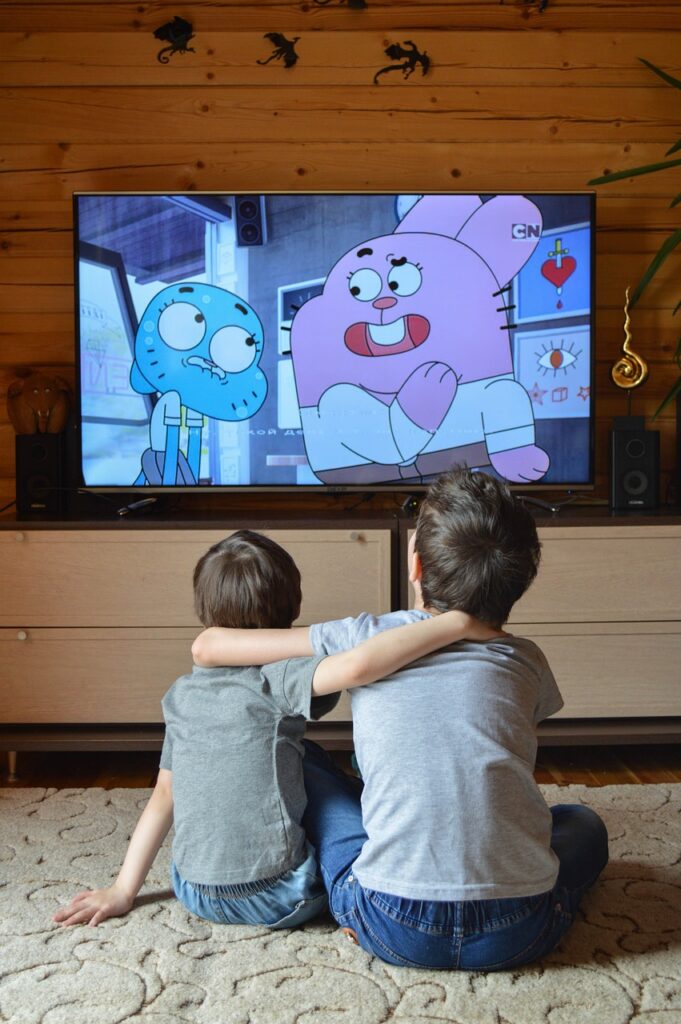

Today, media characters often step into that same imaginary space. Whether it’s a cartoon animal who throws birthday parties or a superhero who talks directly to the screen, kids treat these characters as if they’re real. When characters act like humans—playing, showing feelings, or needing help—children respond in kind, using their imagination to fill in the gaps (Calvert & Richards, 2014). They talk to them, comfort them, and even feel comforted in return.

It’s not just in their heads, either. Many shows are designed to prompt interaction. Characters pause for kids to answer a question or encourage them to participate in some way, and kids genuinely respond as if the character is listening (Lauricella, Gola, & Calvert, 2011). These interactive moments can even help with story comprehension and problem-solving (Calvert et al., 2007), proving that these parasocial exchanges are more than just make-believe.

What Exactly Is a Parasocial Relationship?

In a world filled with screens, subscriptions, and scrolls, many of us are forming surprisingly strong emotional bonds—not with friends or family, but with people we’ve never met. Maybe it’s a favorite YouTuber, an animated sidekick, or even a reality TV contestant. These are called parasocial relationships—those one-sided connections where you feel close to someone who doesn’t even know you exist. And while they might seem like “just feelings,” they can play a profound role in our emotional lives.

The term Parasocial Relationship was coined by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956 (Chung and Cho, 2017). Parasocial relationships are psychological relationships people tend to experience around celebrities and other performers, especially on online platforms. They start considering these performers as their friends or even their lovers despite no evidence of that and limited interaction with them. These people are under the illusion of a reciprocal relationship where no such thing exists.

The concept goes way back, but social media has made it explode. Instead of admiring celebrities from afar, we now follow influencers who share everything—from their skincare routines to their heartbreaks. They feel relatable. Intimate. Almost… real. You might feel like they understand you, inspire you, or even comfort you—without any direct interaction. That’s the heart of a parasocial bond.

How Parasocial Bonds Begin—Even in Childhood

Kids are especially tuned into these relationships. Bond and Calvert (2014) found that children as young as six months can form parasocial connections with their favorite characters. Through parent surveys, they identified three core ingredients:

- Character Personification – Does the child believe the character thinks and feels?

- Attachment – Does the character bring comfort or a sense of safety?

- Social Realism – Does the child believe the character is real?

But it’s not that simple: just watching a show isn’t enough to build these bonds. What truly strengthens them are things like pretend play with character toys, watching the same content over and over, and, most importantly, parental encouragement—when adults lean into the magic and help children emotionally connect with the characters. Of all the factors, parent scaffolding had the biggest influence on deepening the bond.

So next time a child hugs a stuffed version of their favorite TV friend or plays out scenes from a show, remember—it’s more than adorable. It’s meaningful emotional learning in action.

Learning Through One-Sided Connections

Parasocial relationships aren’t just feel-good fluff—they’re learning tools. According to Calvert (2015) and Calvert & Richards (2014), when children observe characters interacting—say, solving problems together or showing kindness—they’re picking up social cues, empathy, and conflict resolution skills. That’s straight out of Bandura’s (1977) social cognitive theory, which says we learn by watching others.

Even language acquisition gets a boost. A study by O’Doherty et al. (2011) revealed that children can learn new words just as effectively from on-screen character interactions as from real-life exchanges. So when your kid picks up vocabulary from a talking puppet? That’s real learning, not just screen time.

Inside the Child’s Mind: What Kids Really Feel

To get inside children’s heads, researchers like Richards and Calvert (2014, 2016) adapted earlier surveys to be kid-friendly. They found something touching: kids didn’t just admire characters—they cared for them. They wanted to feed them, protect them, and help them feel better. That kind of empathy and emotional engagement suggests that parasocial connections are more than passive viewing—they’re relationships children actively invest in.

Gender also plays a role. Children tended to favor characters that matched their own gender, as found by Calvert et al. (2003). And when older kids (ages 7–12) were asked about their favorite characters, Hoffner (1996) discovered some interesting patterns: boys admired intelligence, while girls valued attractiveness. These weren’t just superficial preferences; they influenced how kids emotionally connected with characters and how deeply those bonds ran.

Over time, traits like strength for boys and beauty for girls became recurring themes in how children chose their “favorites” (Reeves & Greenberg, 1977; Hoffner & Cantor, 1985). Meanwhile, Rosaen and Dibble (2008) found that kids who believed a character was real were more likely to develop strong parasocial ties with them.

Parasocial Relationships in the Age of Influencers

Fast forward to today, and parasocial connections have only gotten stronger. Influencers and vloggers don’t just perform—they share their lives. From heartbreaks to morning routines, they invite followers into their world. And followers respond with loyalty, empathy, and sometimes even grief or heartbreak when those influencers change or leave.

The good news? These relationships can promote mental health, encourage positive attitudes, and even help people feel less alone. For teens and adults, parasocial bonds can be a safe space to explore identity, find comfort, or reduce anxiety.

But there’s a downside, too. When we compare ourselves to these carefully curated lives—filtered, polished, and staged—it can feed insecurity and unrealistic expectations, especially for adolescents still figuring out who they are.

So… Are Parasocial Relationships Good or Bad?

They’re both. Like any relationship, even the one-sided ones, parasocial connections can uplift us or bring us down. What matters is how we engage with them—mindfully, or passively. And they’re not a passing fad. They’re deeply human—rooted in our desire to connect, to care, and to feel understood.

Whether it’s a child waving at a cartoon friend or an adult feeling inspired by a podcast host, these emotional connections say something powerful about the open-hearted nature of humans. And maybe, just maybe, they show that even in a digital world, our capacity for connection still runs deep.

Measuring the Unseen Friendships

So how do researchers study a relationship that only feels mutual? Psychologists like Bond and Calvert (2014a) have developed tools to measure how children relate to media characters. They identified three major ingredients: how much kids treat the character like a real person (personification), how attached they feel (attachment), and whether they think the character is real or pretend (social realism).

Interestingly, this bond is stronger when kids are focused on their absolute favorite character. In one study involving toddlers and Elmo (because who else?), researchers found strong patterns of personification and attachment, though kids had a harder time deciding if Elmo was “real” when he wasn’t their top pick (Richards & Calvert, 2015).

What influences these bonds? Quite a few things. When parents encourage these relationships, buy character toys, and replay the same shows, it all adds up. And the more kids “interact” with characters on screen, the deeper the bond gets (Bond & Calvert, 2014a).

Kids Know Best (But Sometimes We Don’t Ask Them)

Of course, it’s one thing to ask parents about their child’s media favorites—but what about asking the kids themselves? Richards and Calvert (2016a) tried exactly that. They created a child-friendly survey using smiley faces to explore kids’ own feelings toward their favorite characters.

The results were fascinating. Kids talked about characters like friends—thinking they might get sad, hungry, or feel left out (Calvert, Richards, & Kent, 2014; Gola et al., 2013). But here’s the twist: Only about 30% of parents could correctly name their child’s favorite character. That mismatch raised some red flags about relying solely on parent reports.

And while kids were good at sharing their feelings of attachment and friendship, their understanding of whether characters are real or pretend was a little shaky—though it improved as they got older (Richards & Calvert, 2017).

References:

- Bond, B. J., & Calvert, S. L. (2014). A model and measure of U.S. parents’ perceptions of young children’s parasocial relationships. Journal of Children and Media, 8 , 286–304.

- Bond, B. J., & Calvert, S. L. (2014a). A model and measure of U.S. parents’ perceptions of young children’s parasocial relationships. Journal of Children and Media, 8, 286–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.890948.

- Bond, B. J., & Calvert, S. L. (2014b). Parasocial breakup among young children in the United States. Journal of Children and Media, 8, 474–490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 17482798.2014.953559.

- Calvert, S. L. (2015). Children and digital media. In R. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Ecological settings and processes in developmental system 7th ed., pp. 375–415). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Calvert, S. L., & Richards, M. (2014). Children’s parasocial relationships with media characters. In J. Bossert, A. Jordan, & D. Romer (Eds.), Media and the well being of children and adolescents . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Calvert, S. L., Kotler, J. A., Zehnder, S., & Shockey, E. (2003). Gender-stereotyping in children’s reports about educational and informational television programs. Media Psychology, 5 , 139–162.

- Calvert, S. L., Richards, M. N., & Kent, C. (2014). Personalized interactive characters for toddlers’ learning of seriation from a video presentation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 148–155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2014.03.004.

- Calvert, S. L., Strong, B. L., Jacobs, E. L., & Conger, E. E. (2007). Interaction and participation for young Hispanic and Caucasian children’s learning of media content. Media Psychology, 9(2), 431–445.

- Calvert, S.L. & Richards, M.N. (2014). Children’s parasocial relationships with media characters. In J. Bossert (Oxford Ed.), A. Jordan & D. Romer (Eds.). Media and the well being of children and adolescents. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. (2017). “Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Celebrities on Social Media: Implications for Celebrity Endorsement”. Psychology & Marketing. 34 (4): 481–495. doi:10.1002/mar.21001. S2CID 151937167.

- Gola, A. A., Richards, M. N., Lauricella, A. R., & Calvert, S. L. (2013). Building meaningful relationships between toddlers and media characters to teach early mathematical skills. Media Psychology, 16, 390–411.

- Hartup, W. (1989). Social relationships and their developmental significance. American Psychologist, 44, 120–126.

- Hoffner, C. (1996). Children’s wishful identifi cation and parasocial interaction with favorite television characters. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 40 , 389–402.

- Hoffner, C., & Cantor, J. (1985). Developmental differences in responses to a television character’s appearance and behavior. Developmental Psychology, 21 , 1065–1074.

- Lauricella, A., Gola, A. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2011). Meaningful characters for toddlers learning from video. Media Psychology, 14, 216–232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2011.573465.

- O’Doherty, K., Troseth, G. L., Shimpi, P. M., Goldenberg, E., Akhtar, N., & Saylor, M. M. (2011). Third-party social interaction and word learning from video. Child Development, 82 , 902–915.

- Reeves, B., & Greenberg, B. S. (1977). Children’s perceptions of television characters. Human Communication Research, 3 , 113–127.

- Richards, M. L., & Calvert, S. L. (2016a). Parent versus child report of young Children’s Parasocial relationships. Journal of Children and Media, 10, 462–480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2016.115750.

- Richards, M. L., & Calvert, S. L. (2017). Measuring young children’s parasocial relationships: Creating a child self-report survey. Journal of Children and Media, 11, 229–240.

- Richards, M. N., & Calvert, S. L. (2014, August). Measuring young children’s parasocial relationships with media characters. Poster presented at American Psychological Association Annual Conference, Washington, D.C.

- Richards, M. N., & Calvert, S. L. (2015). Toddlers’ judgments of media character source credibility on touchscreens. American Behavioral Scientist, 59, 1755–1775. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0002764215596551.

- Richards, M. N., & Calvert, S. L. (2016). Parent versus child report of young children’s parasocial relationships in the United States. Journal of Children and Media . doi:10.1080/17482798.201 6.115750.

- Rosaen, S. F., & Dibble, J. L. (2008). Investigating the relationships among child’s age, parasocial interactions, and the social realism of favorite television characters. Communication Research Reports, 25 , 145–154.Bond, B. J., & Calvert, S. L. (2014a). A model and measure of U.S. parents’ perceptions of young children’s parasocial relationships. Journal of Children and Media, 8, 286–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.890948.

- Singer, D. G., & Singer, J. L. (2005). Imagination and play in the electronic age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.